Peace and patience are the ways to win master strategist Zuma’s game

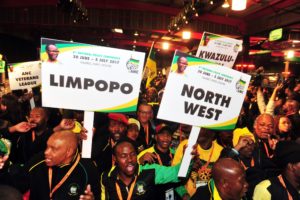

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA – JULY 03: President Jacob Zuma during the African National Congress (ANC) 5th national policy conference at the Nasrec Expo Centre on July 03, 2017 in Johannesburg, South Africa. The conference is a gathering of about 3500 delegates from branches across the country to discuss the party’s policies going into the elective conference in December, where changes and new policies will be ratified. (Photo by Gallo Images / Beeld / Deaan Vivier)

What happens if Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma wins this weekend?

Let’s consider some strategies.

What emerged in past weeks is a tale of two voting blocs.

The “urban” faction understands business and economics, and generates 60% of government income in Gauteng alone.

The “rural” faction is de-industrialised and has come to depend on a politics of patronage. State capture, to them, merely guarantees continued access to state resources.

So an environment has been generated that is divorced from economic realities and amenable instead to rhetorical ploys.

Proceeding from that, Zuma’s recent castigation of the KwaZulu-Natal national executive committee for allowing 184 Cyril Ramaphosa delegates indicates he is falling short of his planned tally. Soon after, KwaZulu-Natal pressured Gwede Mantashe for an extra 100 votes.

Since that would exceed their proportion of representation by 3%, Mantashe refused.

Two days later, the Free State went ahead with its provincial general council, ignoring the court’s instruction that 28 branch general meetings need to be rerun first.

As many expected, at the first sign he might lose, Jacob Zuma began to collapse the conference.

But did he also put another plan into motion?

Two legal experts confirmed last week that validity of the provincial general councils rest upon correct procedure at branch general meetings.

Hence either the courts will interdict Free State attending the ANC conference, or the conference can be invalidated post hoc.

But if Free State delegates don’t go, the 480 delegates lost will give Ramaphosa victory, so Zuma would appeal the decision.

If they do go and Dlamini-Zuma wins, Ramaphosa will appeal the decision. Legally, thus, the conference is already invalidated.

That signals a worrying change in Zuma’s approach to the judiciary. It’s ANC policy to accept the judgment of the courts when internal processes have been exhausted.

But the Free State’s actions raise an overlooked issue. In a captured state are the courts’ decisions enforceable? The police service now acts for the executive first (i.e. Zuma).

So the Free State’s action plays a card that Zuma has had for years.

Doubtless he avoided doing so since he was utilising legal processes in his own favour, to paralyse his opposition.

But the Free State provincial general council reveals that he thinks that the Judiciary is toothless.

Why would he show his hand so obviously? Clearly, he is running out of the usual options. But that is a cause for greater concern, because his remaining options are frankly worrying.

To be clear: Zuma is playing for high stakes.

An outright loss to Ramaphosa might result in the tracking down of all the loot allegedly pilfered by the Zuptas to return the Zuma clan to impoverishment (a key reason Dlamini-Zuma will protect Zuma).

It is also my opinion that Zuma, trained in war, lacks conventional moral boundaries, and if he is pushed to stronger options he will employ them. So what stronger options does he have?

Here it is crucial that the opposition and civil society be imaginative. To date, they have steadfastly held Zuma to the law: that must not change since the law is immutable.

Nothing Zuma can do in the “ordinary” course of events will permit him to not step down in 2019 as South Africa’s president. But what about “extraordinary” events?

It has recently been wondered whether Zuma would enact a formal coup.

It is my opinion that is not a direct option, since the rank-and-file would not act against their own people. Doing so would dispel the ideals that most South African still believe in.

Also, the MK veterans came out strongly against Zuma, and any attempt by South Africa’s soldiers to overstep civil liberties of the South African people would find a trained army arranged against them.

Just so, the African Union would likely not accede to a coup here as they did in Zimbabwe.

But Zuma is a strategist and there might be indirect ways forward. Let’s consider scenarios.

Interestingly, it is unlikely that Ramaphosa could win the vote. Since that alone would undo Zuma – for Ramaphosa would be ANC leader during the appeals, and could use delaying tactics in court himself.

If Zuma is uncertain he will win, he will ensure no vote happens, i.e. the conference collapses.

Suppose the vote proceeds and Dlamini-Zuma wins. If Ramaphosa’s supporters initiate legal action, Zuma simply adopts his familiar strategy of delay by appeal.

In that case either Dlamini-Zuma will be ANC leader subject to a later court decision, or Zuma will remain ANC leader until appeals terminate (i.e. not soon).

During that period enough changes could be made within the ANC that a transition to Ramaphosa would become impractical.

Alternatively, Ramaphosa’s backers could split from the ANC immediately.

They will doubtless judge whether cutting themselves off from the ANC’s internal decision-making would allow Zuma to proceed unchecked as the head of government.

If much damage could be done before 2019 without ANC checks and balances, they might avoid that path.

Another option is that the Ramaphosa faction accepts the poisoned “unity” compromise, which the Zuma faction would accept if it places enough of their faction in high ANC echelons to paralyse Ramaphosa as both ANC and South Africa president.

A fourth option, unnoticed so far, is that Ramaphosa accepts a unity compromise in the short term, but if it doesn’t work his supporters split off just before the national elections.

Judging from the branch general meetings and polls, such a split would ensure that the ANC loses its majority in 2019.

The Ramaphosa side would retain Cosatu and the SACP (i.e. most of the tripartite alliance to woo voters), and if they keep a version of the name “ANC”, would likely still be the largest party. A coalition government could then be formed with other parties averse to state capture (i.e. all of them).

Senior ANC incumbents from Zuma’s faction would doubtless keep their seats in Parliament: but they would have to watch as legal action begins against them in full.

But Zuma knows all that. What stronger tools he could mobilise? In the longer term, of course, he could attempt to subvert the 2019 election.

Should that process begin, civil society and opposition should cry out early for external monitoring of electoral processes.

But a medium-term option has surfaced – and here we return to the chance of “extraordinary” situations above.

Here Dlamini-Zuma’s comments earlier this week to a KwaZulu-Natal audience (e.g. that many black people live worse than white people’s dogs) seem more scripted than opportunistic. Such a strategy shifts the diatribe against white monopoly capital directly against “whites”, to encourage violence.

In the medium term, if the situation can be claimed to be untenable enough, the army could indeed be mobilised in order to “protect” the nation. Since South Africa’s industrialised areas are small and separate from the primary Zuma voter base, this is feasible.

In short, if Zuma causes a state of emergency, then by declaring a state of emergency he could initiate a military regime.

Hence the moment such a strategy is sniffed out, civil society and media should act to deny each claim.

All rhetoric will need to be countered and defused early on, directly in the areas that Zuma is likely to appeal to.

But this risk may apply in the shorter term, and even soon. Zuma’s own appeals to “unity” could be seen as his advance justification that despite his pleas the opposition insisted on destabilising the conference, and damaging the ANC (why, for example, does David Mabuza himself still allegedly insist on “unity” as a vote rather than Dlamini-Zuma, to whom his votes are allotted?).

Provided such a “reason” can be supplied, Zuma could indeed send in the army or police, again in the guise of imposing order.

That would be the first step to a state of emergency. And of course, such states too can be delayed and extended.

That is why it is imperative that if anyone attempts to cause a collapse at the conference, the Ramaphosa faction resist all invitation to violence. The response needs to be obvious pacifism to avoid justifying a physical intervention.

Of course, all these scenarios mean the conference is not the finish line; the anti-Zuma marathon likely only ends in 2019. But a fundamental shift is occurring.

Zuma’s usage of the courts as a delaying tactic has served him excellently. But time is no longer on his side.

Everyone else, however, has lots of time since the laws are timeless. Zuma, Lynne Brown et al might indeed pillage our state resources until 2019.

But provided that the opposition and civil society keep holding them to the law, and given a peaceful society in which Zuma has no chance to claim extraordinary measures, he will need to step down in 2019.

Then every last red cent can be tracked down, with the help of foreign agencies, and returned to South Africans.

• Dino Galetti is a post-doctoral researcher, currently affiliated with the University of Johannesburg and Yale University.

This article first appeared on City Press Online.

(Photo credit: Gallo Images / Beeld / Deaan Vivier)