Is Ramaphosa the ethnic unifier the ANC needs?

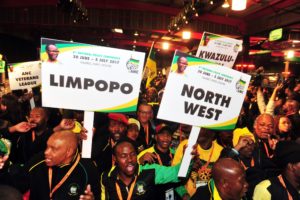

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA – JULY 01: President Jacob Zuma and his deputy Cyril Ramaphosa during the African National Congress (ANC) 5th national policy conference at the Nasrec Expo Centre on July 01, 2017 in Johannesburg, South Africa. The conference is a gathering of about 3500 delegates from branches across the country to discuss the party’s policies going into the elective conference in December, where changes and new policies will be ratified. (Photo by Gallo Images / City Press / Muntu Vilakazi)

Nelson Mandela memorably preferred Cyril Ramaphosa as his successor to deal with the perception that the ANC – and by extension – the country was run by Xhosa people.

There probably was another reason: Ramaphosa had gained prominence as a leader at Codesa. No doubt the negotiation skills he had developed while he was the general secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers worked well for the ANC delegation at Codesa.

Thabo Mbeki had his strengths. By the time of the Codesa negotiations in the early 1990s, he had already won the confidence of Afrikaner leaders. At the behest of Oliver Tambo in the late 1980s, he had met and impressed them in London where the seeds for “talks about talks” were planted. Mbeki invited Jacob Zuma to some of the meetings. In one meeting Zuma complained about “too much corruption in Africa”.

Mbeki worked with Tambo and carried his instruction to talk to Mandela by phone while he was still in prison. The apartheid regime had already hinted at willingness to talk, but Mandela had insisted that he wanted the ANC leaders in exile to be involved and he could only take instructions from them.

It would be surprising if Mbeki had not, in a way, seen himself as a natural successor by virtue of his closeness to Tambo and having had the privilege to take direct instructions from him. It was not a small matter that he was an integral part of the trio that included Tambo and Mandela who, in the main, decided the approach the ANC needed to take towards the negotiations with the apartheid government.

The fact that all three of them were Xhosa speaking didn’t seem to bother Mbeki. If he was bothered he never showed it. Which might also explain why he never obsessed about using his position as president to develop his village or build a mansion in rural Transkei.

His anointment by Tambo might have come through in 1989 when Tambo said to him: “Look after the ANC and make sure we succeed. You will know what needs to be done.”

Despite Mandela’s wishes and ethnic considerations, it would have been difficult for Ramaphosa to fight a battle with someone so close to Tambo, a leader who commanded near-universal respect.

Ramaphosa, who gained prominence in the United Democratic Front and trade union movement, had no option but to wait for his time. This could be another plausible explanation for Ramaphosa’s decision to shift his focus to business. The popular view is that he was elbowed out of the 1997 leadership race.

Ramaphosa gave credence to the popular view by showing lack of appetite to contest the presidency even when there was a leadership crisis that needed a unifier. Kader Asmal desperately wanted him to enter the Polokwane presidential race in 2007 to serve as a “unity candidate”. He failed to convince him.

His supposed lack of appetite – some say sulking – worked for him because when he was invited by Jacob Zuma’s campaigners to join his slate in Mangaung in 2012, they strongly believed they were using him only temporarily. He had no constituency and was therefore not a threat to their ambitions beyond 2017.

The people who invited him onto Zuma’s slate almost immediately started a succession plan for Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma. They were never interested in seeing whether Ramaphosa would demonstrate signs of being a good leader. Clearly, they were not looking for a good leader to succeed Zuma. They were looking for anyone who would perpetuate Zuma’s rule. Ramaphosa would remain some sort of accessory to provide credibility to Zuma’s successor. So they thought.

Mandela’s ethnic consideration aside, there was a very negative campaign from KwaZulu-Natal’s traditional leaders. This tribal-based negativity was told by FW de Klerk in his autobiography The Last Trek: A New Beginning. In January 1994, President De Klerk hosted traditional leaders from KwaZulu-Natal at the Union Buildings. Among them were King Goodwill Zwelithini and Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi.

They were very concerned that the proposed Transitional Executive Council, the product of Codesa negotiations, would take over the administration of KwaZulu and thus compromise their wish to curve an independent Zulu kingdom. One of the princes told De Klerk in the meeting: “We tolerated British rule. We tolerated rule by you [Afrikaners]. We tolerated apartheid, but we will not tolerate rule by the Xhosas. We want our sovereignty!”

De Klerk’s quotable Zulu prince was totally ignorant. Zulu wars, dating back to the pre-colonial era, are well known. The suggestion that they “tolerated” all these things, including apartheid, is obviously false.

But De Klerk couldn’t miss the emotions around the ethnic question. He therefore gave it prominence in his book. He wrote that the delegation was particularly contemptuous of Ramaphosa.

The Transitional Executive Council was seen as a product of Ramaphosa’s negotiation tactics. The anger was directed at him. The princes, according to De Klerk, found it inconceivable that “Venda (sic) should dare to think that he could come impose his will on sons of heaven [the Zulus]”. Strangely, there have been no objections to the tribalism recorded in De Klerk’s book.

Ramaphosa is, however, not stuck in narrow regionalism. He visited Zwelithini recently, presented him a special breed of cattle and they had a good time together. He won his blessings. He got similar blessings from traditional leaders in the Eastern Cape.

Though not entirely fluent, he speaks Zulu when he’s in KwaZulu-Natal, Xhosa in the Eastern Cape, Tsonga and Sepedi in Limpopo. He hardly speaks Venda, his mother tongue. Symbolically, it’s a good thing as it has a unifying feel about it.

Will delegates at the national conference care about his appreciation of the country’s linguistic diversity and give the ANC its first truly multilingual president?

– Mkhabela is a fellow at the Centre for the Study of Governance Innovation (GovInn) at the University of Pretoria.

(Photo credit: Gallo Images / City Press / Muntu Vilakazi)