Mantashe’s 10 years of keeping it together

PRETORIA, SOUTH AFRICA – NOVEMBER 11: ANC secretary-general Gwede Mantashe and Zizi Kodwa during the party’s special National Executive Committee (NEC) meeting at the St Georges Hotel on November 11, 2017 in Pretoria, South Africa. The national executive members convened to discuss, among others, feedback from the party’s Veterans League conference and the recent Eastern Cape provincial conference. (Photo by Gallo Images / City Press / Tebogo Letsie)

ANC secretary-general Gwede Mantashe recalls that he was only three months into his first term of office when the ANC Youth League, then led by Julius Malema, showed him rolling hands – a sign indicating a call for substitution in football matches.

In a later youth league national executive committee meeting in Tshwane, an unfazed Mantashe rolled hands alongside his critics.

“They wanted change and I gave it to them,” he boasted at a media briefing a few years later, after the ANC expelled Malema for bringing the party into disrepute.

“Everywhere I go, I fire people who do not obey the law,” Mantashe told City Press this week in an interview marking the end of his 10 years of service as secretary-general. Before his election to the ANC’s top six in Polokwane in 2007, he was chairperson of the South African Communist Party (SACP), which is notorious for expelling defiant party members.

As general secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), he was blamed for the firing of Joseph Mathunjwa and the subsequent formation of the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, which threatened to decimate the NUM in the platinum belt. But Mantashe shrugs the allegations off, saying that Mathunjwa never appeared before him for a disciplinary hearing.

With the Congress of the People (Cope) and Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters breaking off from the ANC under his watch, does he have any regrets?

“I have no regrets about firing Malema. We only fired Malema and others left with him, so that was not a splinter,” he says.

“Yes, Cope was a splinter. But it was premeditated and was in formation on the way to Polokwane.”

Having come into power on a leftist ticket, there was a lot of expectation that Mantashe would be instrumental in pushing the ANC’s policy to the left. He disagrees: “The ANC has a very entrenched system. You go to policy conference and follow internal structures before policy is formed.”

In any case, he retorts: “I am not a faction of the SACP in the ANC, I am a communist secretary-general of the ANC.”

The ANC does influence government, he says. “We call them at the [ANC national executive committee] lekgotla and we have everybody there. And from time to time we call in a minister, who comes with some of the operatives. So we influence government in that way, but the actual running of government is not done in Luthuli House,” Mantashe says. He is often punted as South Africa’s prime minister because of the powers vested in his office.

“We then take the heat because when government operations misfire, it reflects on the ANC. That is why we must answer about state capture and Nkandla. All those things have not been done in the ANC, but we have to absorb the heat.”

“We have dented the brand ANC”

He says his first five year term – which ended in 2012 – was wonderful. “We did many things and effected changes that impacted on the real lives of the people.

“My flagship change was the separation of basic education from higher education.”

His second highlight has been establishing the department of rural development, which he says still has to reach its full potential.

“It should have done much better. I think the process got derailed to focus on many things. Maybe it was a mistake to mix it with land redistribution.”

He decries the fact that his second term, currently still in effect, has lacked momentum. “We had to deal with a number of issues regarding Nkandla, like the Public Protector’s report and Constitutional Court ruling, as well as state capture.”

That contributed to the ANC’s electoral decline, he concedes. “The opposition managed to change the local government narrative and focus on national issues, even though, for the work we do at local government level, we cannot be faulted. We have done well in terms of changing the lives of people in communities.”

He says his second term has been painful as it has focused on what was damaging the ANC’s image.

“To a great extent in this term, we have dented the brand ANC. That is the pain I’m going through and that is what we dealt with most of the time.”

That was not the only thing that changed. Previously, he would have been able to go and see President Jacob Zuma without hassle.

“In the second term that all died. All of a sudden, I deal with the president officially, in meetings of officials.”

Members of the ANC’s executive committee have described Zuma as a bully.

“Zuma is a bully in the sense that when he has a view, sometimes he says that view at the end of the meeting when there is no space to engage. He will put it as part of the closing remarks and bulldoze things through in that way,” Mantashe says.

But he denies claims that Zuma uses his struggle credentials to intimidate his colleagues.

Mantashe rejects the notion that he is the ANC’s CEO. “If people want to hit you, they give you titles that are not yours. In the ANC I am responsible for administration and that is it. I am just the head of administration. People who want to give me undue high positions want to attack me. It is not honest.”

He rates the relationship he has with Luthuli House staff highly, even though he has been accused of inappropriate behaviour towards female employees.

“One of the things that you will be told when I’m no longer in Luthuli House is the ability of the secretary-general to walk floor to floor once a week. I know every person who leaves his jacket in the office and then isn’t there for two days. I take time, once a week, to take in all the floors. I have relationships with my staff. We do not relate as a boss and a servant, but we relate as comrades. That is the spirit.

“They will talk about me giving my staff hugs and taking selfies. Nobody will say I groped or I screwed anybody. You will not find that.”

He sees himself as a father figure to his staff.

“I have the same relationship with my kids. All four of them, the eldest being 36 and the youngest 20. They do not call me daddy, they call me comrade.”

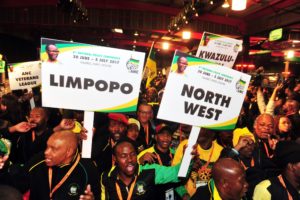

As his term winds down, Mantashe is preoccupied with making sure the national conference is successful. He dismisses fears that it may collapse because they have “planned smart”.

This article first appeared in City Press on 10 December.

(Photo credit: Gallo Images / City Press / Tebogo Letsie)